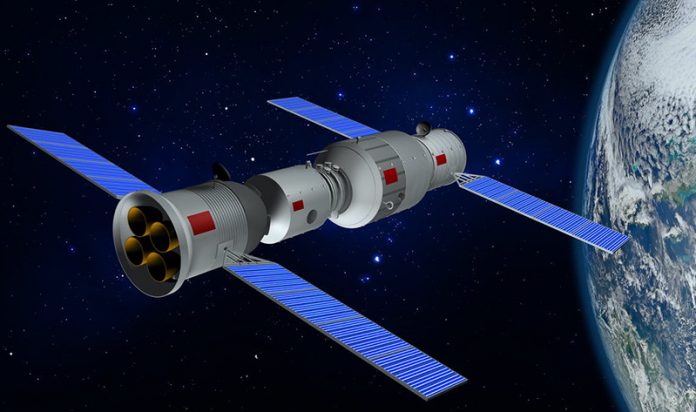

China launched Tianhe-1, the first and main module of a permanent orbiting space station called Tiangong (Heavenly Palace 天 宫), on April 29. Two additional science modules (Wentian and Mengtian) will follow in 2022 in a series of missions that will complete the station and allow it to start operations.

While the station is not China’s first – the country has already launched two – the modular design is new. It replicates the International Space Station (ISS), from which China was excluded.

There are many reasons for China to invest in this costly and technologically challenging project. One is to conduct scientific research and make medical, environmental and technological discoveries. But there are also other possible motivations, such as commercial gains and prestige.

That said, Tiangong does not aim to compete with the ISS. The Chinese station will be smaller and similar in design and size to the former Soviet Mir space station, meaning it will have limited capacity for astronauts (three versus six on ISS).

After all, it doesn’t have as much money behind it as the ISS and there are not as many countries involved. If anything can be called the UN in space, it is the ISS, which has as collaborators former cold war enemies (US and Russia) and old friends (Japan, Canada and Europe). Over its two decades and counting of service, the only permanent human outpost in space has hosted about 250 astronauts from 19 different countries, carrying out hundreds of spacewalks and thousands of scientific experiments.

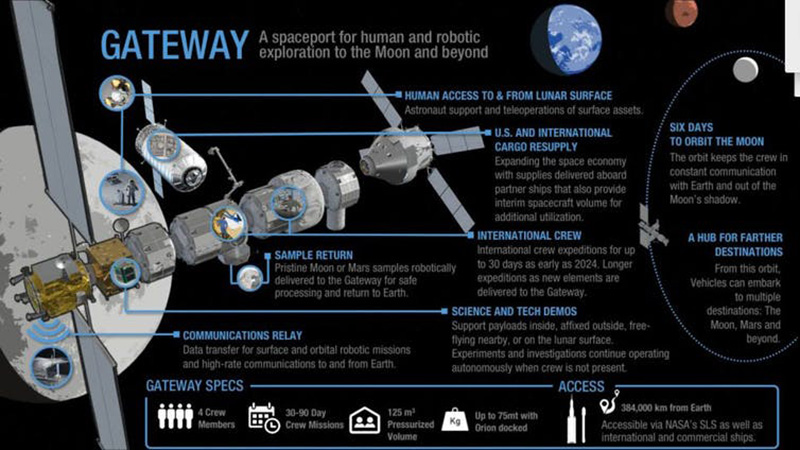

But the ISS is coming to its natural end. It’s scheduled to be decommissioned after 2024 to leave place for the Lunar Gateway, a small outpost that will orbit the Moon. This is an international initiative part of the US-led Artemis Programme that again sees China excluded.

Toward a Chinese monopoly?

Until the gateway is launched, however, Tiangong – which will be placed in lower Earth orbit and have an expected life of 15 years – will probably remain the only functioning space station. Some worry this makes it a security threat, arguing its science modules could be easily converted for military purposes, such as spying on countries. But it doesn’t have to be this way and, if things go as planned, it won’t be.

China may use this opportunity to win back trust and attract international collaboration. This may be particularly important given Nasa’s criticism following the recent Chinese out-of-control rocket that plunged into the Indian Ocean. There are signs the country is trying to be more open, having already declared Tiangong will be open to host non-Chinese crews and science projects. Astronauts from Europe’s space agency, Esa, have in fact begun training with Chinese “taikonauts”, and international projects have been included in the station’s first approved batch of selected experiments.

Tiangong might not remain alone for long either. Supported by Nasa, private corporations have started designing their own orbital modules, from Bigelow Aerospace’s inflatable habitat B330 to the commercial laboratory and residential infrastructure built by Axiom. Even Blue Origin has shown interest in building a space station. The Russians seem to like the idea, too – they already have plans for a luxury space hotel.

What’s more, the already extended ISS lifespan may be further prolonged, although there are many issues surrounding its end date.

The Lunar Gateway

Tiangong may not be alone for long, however, as the Lunar Gateway will be launched eventually. In its basic conception, the Lunar Gateway will serve as a science laboratory and short-term habitation module. It will then act as a hub, allowing for spacecraft and rovers to resupply during their multiple trips to the Moon. The first launch is planned as early as May 2024 with SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket, taking the essential modules. It should be operational a few years later.

Compared to the ISS, the Gateway will be smaller and more nimble. Of the original ISS members, only four (US, Europe, Japan and Canada) are part of the Gateway.

For now, Russia has not joined, due to the controversies surrounding the Artemis programme, which many countries believe is too US-centric.

This is another opportunity for China. It has already started collaborating with other countries on recent space projects. More is coming. In March 2021, it signed an agreement with Russia’s space agency Roscosmos to build a joint Russian-Chinese research facility on the Moon. Having lost its monopoly for manned flights to the ISS due to the successful SpaceX launch in 2020, Russia seems keen to keep its options open for what concerns lunar projects.

Ultimately, space is both challenging and expensive. While it is a way for many countries to show dominance, cooperation has already proved to be more effective than lone endeavours: if anything, the ISS is the best proof that. We know that space exploration can also defuse tensions on the ground, as it did during the cold war.

China’s taking a leading role in the new space race could have a similarly positive effect – especially if the country shows goodwill in helping address a growing security problem in low Earth orbit: how to get rid of space junk.

The article was first published in The Conversation

About the Author

Steffi Paladini is a Reader in Economics & Global Security, Birmingham City University. She is a Former government official and trade commissioner, full-time academic since 2008. Expertise in international trade, space industry, data analysis and sustainable development.

Paladini obtained her PhD in International Relations and Security Studies from City University of Hong Kong, also spending seven years in East Asia as Trade Commissioner.

Among her recent activities is the EU-F7 IRSES – Chinese FDI in the EU “CHEUFDI” (2013-2016), a joint project in agent-based modelling for environmental security and innovation, and an ongoing research on the EU space industry. Her latest book is “The New Frontiers of Space. Economic Implications, Security Issues and Evolving Scenarios”, London: Macmillan, was published in 2019.