By Winnie King

With Britain’s new government still reeling from the potential costs of Brexit, China as the world’s second largest economy is in a position of strength for any future negotiations for direct trade links and agreements. With the new reality of Theresa May placing national security at the centre of her foreign economic policy, how she and Xi Jinping frame dialogue and negotiations will be key.

“This is a Golden era for UK-China relations,”1 Prime Minister Theresa May stated September 2nd on her way to the G20 meeting in Hangzhou, China. The question however, is if this will continue to be the 24 carat gold of the days of Cameron and Osborne? Or have delays and contract amendments linked to Hinkley Point irrevocably tarnished the gleam of relations? If President Xi Jinping’s statement during the G20 Summit is any indication, he is willing to “show patience”, giving Mrs. May time to frame and launch her vision of British foreign policy and economic relations.

As one who seems to keeps her cards close to her chest, the question is what shape will this come in?

Just as China has successfully done, Britain’s China policy should be about advancing and achieving its national interest. Far from an unusual demand, the Americans, Japanese and undoubtedly China, have core objectives that must be maintained. Under Blair bilateral relations were all about humanitarian intervention and human rights. Cameron, on the other hand, had offered a far more commerce-focused approach, unsurprising given the events and costs of the 2008 Financial Crisis. For May however, now saddled with the aftermath of Brexit, a balance must be achieved. While May has an unclear path before her, Britain’s “independence day” must be handled with strategic care – particularly when it comes to advancing Sino-British relations. For both Britain and China this is all about quantifiable benefits.

Mending Fences – It’s all about Trust

It is imperative for the British to remember that the Chinese are not renowned for their patience. The Chinese must also accept that the British are going through a significant upheaval following the June 23rd decision to exit the European Union. As May announced delays and called for a reassessment on China’s flagship project with Britain, a mere week passed before Chinese Ambassador to Britain, Liu Xiaoming responded. With national security concerns entering the mix, and now at the forefront of relations, May has presented what the Chinese deem to be with a dramatic and unwelcome about face. With potentially severe consequences, the linchpin is now Trust—in particular, China’s loss of trust for Britain, its current main European economic partner.

Liu wrote on August 8th in the Financial Times, “Britain is one of the key destinations for Chinese companies seeking to invest overseas…if Britain’s openness is a condition for bilateral co-operation, the mutual trust is the very foundation on which this is built.”2 The loss of this openness, as hinted by May, could see the gates of Chinese capital, investment, and trade relations shut – far from ideal in a Post-Brexit Britain.

China has a long memory, and Britain’s track record is mixed at best. When compared to other European economies, the historical baggage of Britain’s colonial past, the Dali Lama freeze-out of 2012 and the UK’s continued efforts to intercede on Hong Kong’s behalf, for the Chinese the attractive tangibles don’t necessarily outweigh the negatives.

While Hinkley has received the green light, this alone is insufficient. Hinkley is a flagship project only in so far as a significant initial step. The Chinese partners – China General Nuclear Power (CGN) – are targeting Bradwell, Essex as the real jewel of nuclear energy infrastructural projects. Therefore, with the new reality of May placing national security at the centre of her foreign economic policy, how she and Xi frame dialogue and negotiations will be key.

It’s all about Attitude

Critics of Sino-British relations saw the former government as moving too quickly into China’s embrace. Brexit however, offers a new environment within which dialogue and relations can be rebuilt upon a basis of equal status, mutual respect and consistency. It’s a new era for the British – similar to the Chinese and their renowned desire for self-sufficiency and minimising dependency – offering greater scope for enhanced engagement.

Firstly, to be a serious partner, Theresa May’s dream team of Phil Hammond (Chancellor), Boris Johnson (Foreign Secretary) and Liam Fox (Britain’s first Minister for International Trade) needs to establish a strong united front. Any territorial in fighting will be seen as a weakness by the Chinese. She will never succeed if her generals aren’t in place.

Simultaneously, building trust with a new leader and government necessitates that China avoid its longstanding strategy of “divide and conquer” which has been successful in maximising gains from the European Union and its member states. Just as May’s operation plan must secure against this, China must adjust its approach.

Secondly, success necessitates a concerted effort to re-set the vision of British-China relations. Namely, think long-term. It will no longer be about coveting China. Establishing a coherent relationship means Harry Potter, Shakespeare and David Beckham, and Chinese cultural and linguistic tours and exchanges, the cornerstone of both British and Chinese soft power, aren’t going to cut it anymore. For example, while Chinese tourism brings an estimated £500m per annum, selling Britain as cultural and historical icon offers little substance for a long-term and balanced relationship. Furthermore, Global Times editorials labeling Britain “an old and declining empire”3 in 2014, and suggested “mak[ing] London pay the price for when it intrudes into the interests of China”4 in 2013, give every indication that China will also need to shift their approach.

Offering a clear line that the relationship isn’t taken seriously by either participant, Britain not only needs to shake off its image “that the UK is not a big power in the eyes of the Chinese. It is just an old European country apt for travel and study”,5 but China needs to stop minimising Britain’s position in the hierarchy of bilateral relations.

Thirdly, Yes the new British government needs to woo, but more importantly bilateral relations need to enter into negotiations on an equal (not inferior) footing. This is imperative.

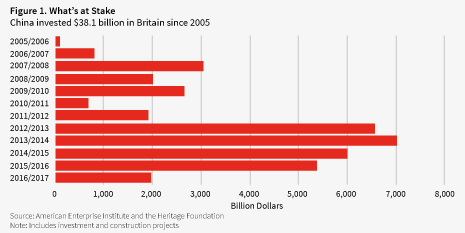

Since 2012/2013, Britain has become China’s top destination for investment. However, beyond parking funds in property purchases May will need to secure the UK’s position as the expected and natural destination, not a grateful one. British technology, skill sets, industrial know how, innovation, research and development, each representing an opportunity for Chinese investment and capital. The proof is in Britain’s tech sector, which secured £3.6bn in venture capital investment in 2015, 70% more than 2014.6 In January 2016 alone, a Chinese VC fund earmarked £500m for UK fintech and biotech startups.7

Know your Audience – Have a Plan

With Britain’s new government still reeling from the potential costs of Brexit, China as the world’s second largest economy is in a position of strength for any future negotiations for direct trade links and agreements. But just as Britain has left the EU’s supranational “development strategy” bed, we should not expect it to jump into a Chinese one.

Success, above all, requires a clear China policy and strategy with identifiable core objectives, something Britain has long been missing. As I’ve written before, in addition to “…showing how Britain can contribute to China’s economic reform… [the government must stress] how China can enhance Britain’s own industrial base and technological comparative advantages – for Britain.”8

Prime Minister May is right in stating that Hinkley does not represent the entire Sino-British relationship. For China however, this was the prize of Xi Jinping’s 2015 state visit. To dismiss its significance would be unwise, and to ignore the potential domino effect costly.

Should CGN’s Bradwell application not succeed, or come to negotiations on purely security terms, both parties must recognise the story has changed. While the Chinese are inherently pragmatic by nature, May ought logically to frame this decision around Brexit – partially resolving China’s concerns that it is the primary target or impetus behind reassessments like Hinkley. Security considerations for Britain’s Critical National Infrastructure now apply to all prospective investors and sectors, including long-standing allies like the French – as seen with EDF and Hinkley Point C.

Overall however, taking this occasion to shift the focus of China-British relations, May must follow through. Inconsistency will do nothing more than undermine any progress. With Chinese investment over the past 3 years predominately in highly sensitive and security-laden sectors however, this raises the question of what this means for Thames Water, BP, East London Airport, and HS2. Moving forward, Cameron and Osborne have left an indelible stamp on British-China relations which May should build upon – including Asian Investment Infrastructure Bank (AIIB) membership, record trade and investment relations, mergers and acquisitions, and positioning the City of London as a central player in China’s currency internationalisation and financial reform process.

The latter is an invaluable opportunity for securing the City’s international footprint and stature after Brexit. With IMF’s efforts to broaden the use of its SDR basket and issue bonds, and Britain topping RMB centres outside Hong Kong (UK RMB payments rose 21% y-o-y in March 2016),9 it is well positioned to participate in a central pillar of China’s current 13th Five year plan: finance and service sector. The opportunities for China’s own objectives are clear.

At the end of 2015 China was Britain’s 6th largest export market. As China’s continues its economic reforms, a relatively underutilised resource has been UK’s domestic businesses – long ready to do business with China. Attracted by an expanding services sector and a market of 1.3 billion consumers, May’s China policy should stress job creation, strategic industrial development, collaboration and investment.

May is being offered an opportunity to assert an enlightened and forward thinking China policy built around Britain’s national interest. And as the Chinese is well aware, this is long overdue. But make no mistake, to take advantage of Britain’s Brexit conundrum will do little more than undermine the longevity and strength of a potentially highly mutually beneficial relationship. This is a time for negotiations as equal partners. Yes, Britain needs China. But it also requires knowing your audience.

This article was originally published on LinkedIN and can be found here and on China Policy Institute: Analysis

About the Author

Winnie King is a Teaching Fellow at the University of Bristol where she specialises in East Asian Political Economy and Sino-EU Relations.

References

1. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/b8bc62dc-5d74-11e6-bb77-a121aa8abd95.html#axzz4JU27kK7x

2. http://lnkd.in/ett3zn7